At first blush, it looks redundant.

The weekend before the U.S. presidential election, crypto-based prediction market Polymarket spun up a contract betting on who will be inaugurated as the next leader of the free world.

As anyone who has paid the slightest bit of attention to crypto or election news coverage this year knows, Polymarket already had a heavily traded contract on which candidate will win the presidential race.

That contract has seen more than $3 billion in trading volume, according to Polymarket, with more than $200 million worth of open interest, or positions outstanding, according to a Dune Analytics dashboard prepared by the user mahdi0077.

There’s a subtle difference between the “winner” contract, which Polymarket has listed since February, and the new “inauguration” one. That difference highlights a challenge facing prediction markets ahead of Tuesday’s vote in a politically polarized, low-trust environment.

Namely: What if the election results aren’t clear shortly after the polls close? Or, if they are clear to one side, what if the purportedly losing candidate disputes them, as Donald Trump did four years ago, leading to the Jan. 6, 2021 Capitol riot? Or if one candidate concedes but then withdraws the concession, as Democrat Albert Gore did in 2000, leading to a Supreme Court case?

There “could be a hornet’s nest about this next week,” Koleman Strumpf, an economics professor at Wake Forest University in North Carolina, told CoinDesk by email last week.

In prediction markets, traders bet on verifiable outcomes of real-world events in specified time frames. Typically, they buy “yes” or “no” shares in an outcome, and each share pays $1 if the prediction comes true, or zero if not. (On Polymarket, bets are settled in USDC, a stablecoin, or cryptocurrency that trades one-to-one for dollars; other platforms, including Kalshi and PredictIt, pay out regular greenbacks.)

As of Monday morning in New York, “yes” shares for Trump winning the presidency traded at 59 cents, indicating the market saw a 59% chance of victory for the Republican candidate. Democrat Kamala Harris’ odds were at 41%.

The rules for Polymarket’s “winner” contract say it will resolve once all three of the Associated Press, Fox News and NBC call the race. However, if all three media outlets haven’t done so for the same candidate by Inauguration Day (Jan. 20, 2025), the market will be resolved according to who is inaugurated.

By contrast, Polymarket’s new “inauguration” contract doesn’t bother with press sources, and will wait until Jan. 20 to resolve. If no one has been inaugurated by then, it kicks the can to Jan. 31. And if no one has been inaugurated by then, both the Trump and Harris “yes” shares will resolve to “no,” and “no” holders for both candidates will collect payouts, which would be an unusual situation.

This is more in line with Kalshi’s presidential contract, which resolves according to who is inaugurated on Jan. 20 (though the fine print says an inauguration doesn’t count if “the first person inaugurated as the President serves only in an acting (i.e., temporary) capacity”).

“There may be disputes among the candidates and media about who wins the election, but only one will be inaugurated as determined by the official Executive Office of the President,” said Jack Such, Kalshi’s head of market research. “For this reason, we believe resolving on inauguration day is the safest choice for our customers because it provides the highest clarity of resolution criteria.”

A Polymarket representative wouldn’t comment for the record.

There are tradeoffs between the two approaches.

“The Polymarket resolution has the benefit of potentially resolving sooner, at [a] time when agreement on the resolution is generally accepted — and this might make it more popular because of the time value of money,” said Aaron Brogan, a lawyer who has studied prediction markets.

(Offsetting the potential opportunity cost of a delayed payout, Kalshi is paying clients 4% interest on open positions, Such noted.)

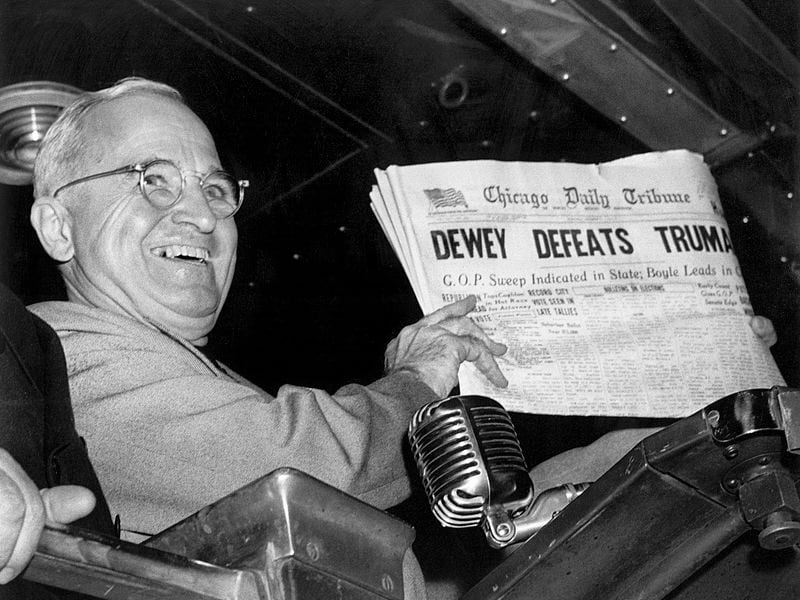

On the other hand, a media outlet could make a call and then reverse it, as the Chicago Daily Tribune did in 1948 following the infamous “Dewey Defeats Truman” headline.

“If the Polymarket contract resolves, and then one of the sources flips, it could be a big headache and a lot of litigation for everyone involved,” Brogan said.

Potentially complicating matters, Polymarket uses UMA, a decentralized oracle service, to resolve markets and referee disputed outcomes. When a dispute arises, UMA token holders debate the matter a day or two, then vote on which side is correct.

An article in The Atlantic last week noted that UMA made a contentious decision earlier this year, resolving Polymarket’s Venezuelan election contract for the opposition leader (who got more votes), despite incumbent Nicolas Maduro reportedly stealing the election. Polymarket has overruled UMA at least once (though not in the Venezuela case).

UMA co-founder Hart Lambur did not respond to a direct message sent on X (formerly Twitter).

Flip Pidot, a prediction market veteran who wrote about 5,000 contracts for PredictIt, said the resolution criteria for Kalshi’s and Polymarket’s main presidential contract “are both bad.”

Kalshi’s criteria, tied to the inauguration, “aren’t necessarily ambiguous (which is the worst possible scenario), but they’re potentially out of sync with the spirit of the market, which is who’ll win the election,” said Pidot, who is now CEO of American Civics Exchange, an over-the-counter dealer of political contracts.

For example, “Trump could win, [then] die or be incarcerated or for some reason decline to be inaugurated, and J.D. Vance would ‘win’ the market (which means all traded outcomes would resolve No),” he said. “Or litigation or outright chaos could reign until past 1/20.”

As for Polymarket’s criteria tied to the three media sources, “any of those three outlets could say it’s ‘indeterminate’ or ‘too close to call’ indefinitely, in which case you’re left with the same inauguration test as Kalshi, which again, doesn’t really match the test that’s being traded (who wins the election),” Pidot said.

“I think everyone’s trying to [punt] past the voting of the electors in December [and] the Congressional tabulation in early January, so that they don’t get snarled in a 2020-like scenario if there’s lots of chaos,” he said. “But the Jan. 6 tabulation is really when someone certifiably wins the election, so that’s what it should be tied to.”