Bitcoin Magazine

Spark Explained Like You’re Five

Some of you may remember an article I published years ago, Understanding Lightning Network Using an Abacus, which I wrote after it became clear to me that many people didn’t fully understand how Lightning works. At the time, my goal wasn’t to explain Lightning’s cryptography or implementation details, but to demystify the core idea behind payment channels. I used the analogy of the abacus to focus on the concept rather than the mechanics. It worked extremely well and people later adopted the abacus analogy to explain Lightning to noobs.

Lately, I’ve been feeling a strong sense of déjà vu.

When discussing Spark, I notice a similar pattern. Some know to say “statechain”, but for most, that’s where the understanding ends. And as with Lightning back then, the problem isn’t a lack of intelligence or effort, it’s simply that the underlying mental model isn’t clear. So I’ll try the same approach again: explain how Spark works conceptually, without getting into cryptographic terminology.

The Two-Piece Puzzle

At its core, Spark allows users to send and receive bitcoin without broadcasting on-chain transactions. The bitcoin doesn’t move on-chain when ownership changes. Instead, what changes is who can jointly authorize their spend. This joint authorization is shared between the user and a group of operators called a Spark Entity (SE).

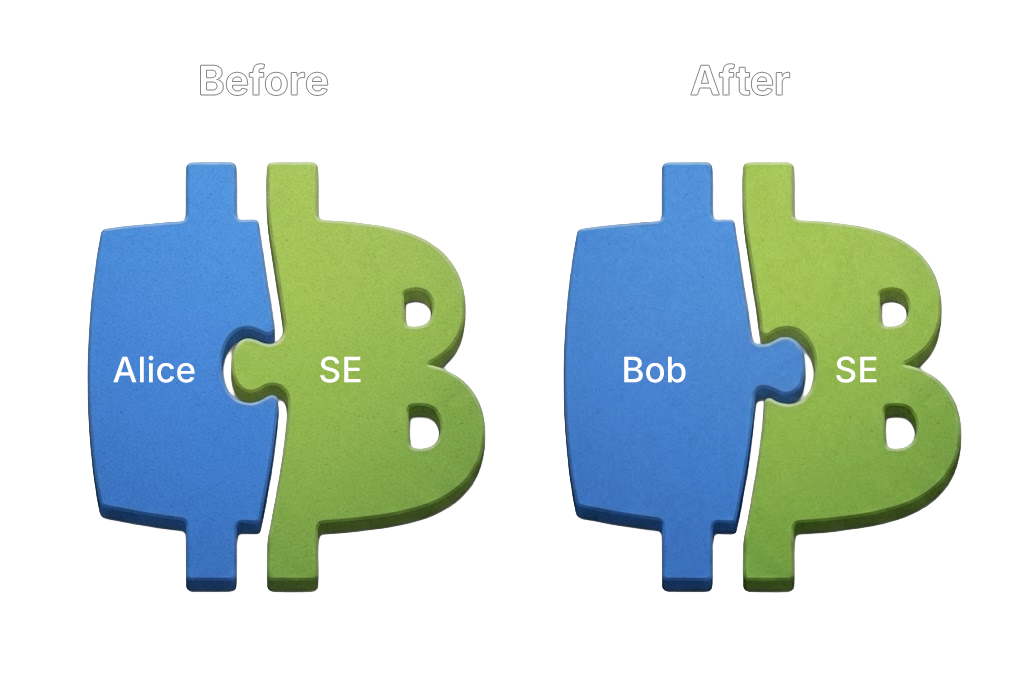

To explain how this works, imagine that spending a given set of bitcoin on Spark requires completing a simple two-piece puzzle:

- One piece of the puzzle is held by the user.

- The other piece is held by the SE.

Only when both matching pieces come together can the bitcoin be spent. A different set of bitcoin will require the completion of a different puzzle.

Now let’s walk through what happens when ownership changes.

Initially, Alice holds a puzzle piece that matches the piece held by the SE. She can spend her bitcoins by combining the pieces and completing the puzzle. When Alice wants to send her bitcoins to Bob, she allows Bob to create a new puzzle together with the SE. Importantly, the puzzle itself doesn’t change: the old and new puzzle have the same shape, but the pieces that compose it change. The new puzzle is designated for Bob: one side is associated with Bob and the other with the SE. From that point on, only Bob’s piece matches the SE’s piece. Alice may still retain her old puzzle piece, but it’s now useless. Since the SE destroyed its matching piece, Alice’s piece no longer fits any other piece and cannot be used to spend the bitcoin. Ownership has effectively moved to Bob, even though the bitcoin in question never moved on-chain.

Bob can later repeat the same process to send the same set of bitcoin to Carol and so on. Each transfer works by replacing the puzzle pieces, not by moving the funds on-chain.

At this point, a question naturally arises: what if the SE simply doesn’t discard its old puzzle piece? In that case, the SE could collude with the previous owner, Alice, and spend Bob’s bitcoin. We need to trust the SE that, when ownership moved from Alice to Bob, it also destroyed its piece of the puzzle. However, it’s important to understand that an SE is not a single party. It consists of a group of operators, and the SE’s side of the puzzle is never held by one operator alone. Replacing the puzzle requires cooperation among multiple operators. No single party can secretly keep an old puzzle active or recreate it later. It’s enough for one operator to act honestly during a transfer to prevent an old puzzle from ever being reactivated.

The key idea is simple: Spark doesn’t move bitcoin on-chain between users. It replaces who holds the valid authorization to spend them. The on-chain bitcoin doesn’t move. What changes is which two puzzle pieces fit together.

To keep this explanation focused, I intentionally didn’t get into Spark’s unilateral exit mechanism. It’s an important part of Spark’s security model, but it would distract from the core idea I want to convey here. What matters is that Spark is not a system where users are permanently dependent on the SE. While everyday transfers rely on joint authorization, Spark also provides users with a way to spend their funds on-chain without requiring the cooperation of the SE. That escape hatch exists by design, it’s just outside the scope of this explanation.

This post Spark Explained Like You’re Five first appeared on Bitcoin Magazine and is written by Roy Sheinfeld.