Bitcoin Magazine

The Avant-Garde and Bitcoin: Decentralized Money Didn’t Come From Nowhere

Bitcoin is a financial tool born of code and cryptography. But seen in a wider frame, it belongs to a cultural lineage more than a century old. Since the 1910s, avant-garde movements have probed questions that later became central to Bitcoin: Who decides value? Can rules replace rulers? How do systems record time, distribute trust or resist authority? Far from appearing out of nowhere in 2009, Bitcoin crystallized ideas that had long circulated in artistic experiments.

You don’t need to like art — or on-chain art — to follow this argument. This article is not a case for “Bitcoin art” but for understanding Bitcoin’s conceptual prehistory. If you are a Bitcoin maximalist, read what follows as the backstory of your protocol’s worldview, not an art-world detour. And if you are an on-chain maximalist, remember that maximalism of any kind denies reality: The logic of Bitcoin was not born on-chain.

Artists tend to surface and stress-test ideas before society at large absorbs them. What they explore in canvases, instructions, networks or number systems often migrates years later into economics, engineering and politics. The point of this article is not to conflate art with Bitcoin, but to show that Bitcoin is the cultural consequence of ideas rehearsed for over a century — ideas about decentralization, protocol, time and value that were already in the air long before they were established in code.

Avant-Garde Futurism: Speed, Systems and the Machine Aesthetic

If the early 20th century’s avant-garde had a launchpad, it was Italian Futurism. Announced in 1909 on the front page of Le Figaro by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the movement exalted “the beauty of speed,” the dynamism of the industrial city and the power of engines, aircraft and modern weapons. It called for the destruction of museums and libraries in favor of an aesthetic reboot — art in step with the machine age.

Futurist painters like Giacomo Balla and sculptors like Umberto Boccioni sought new visual strategies to capture motion: blurred outlines, repeated forms and “lines of force” that rendered figures as vectors in a dynamic system. Boccioni’s iconic “Unique Forms of Continuity in Space” (1913) depicts a striding figure whose body is broken into aerodynamic planes — more like a fluid diagram than anatomy. In sound, Luigi Russolo’s “Intonarumori” (noise intoners) brought the clang of factories and the churn of engines into orchestral performance, turning music into a mechanical event.

Futurism’s legacy is complicated — Marinetti’s later alliance with Italian fascism casts a shadow — but the movement planted seeds of a mindset crucial to later art and to Bitcoin alike: art as the design of systems, not just objects. The Futurists embraced rhythm, repetition, serial processes and the deliberate use of technology as a driver. In effect, they imagined culture running on protocols — machines with outputs defined by rules and cycles.

The Futurists embraced the rhythm of machines, the pulse of the assembly line, the precision of the stopwatch. Bitcoin transposes that rhythm into economics: Value emerges not from decree but from a timed, rule-governed process distributed across the network. Futurism never imagined digital money, yet it prepared the ground by making repetition and system-thinking feel natural.

Dada: Anti-Art as an Attack on Systems

Amid the chaos of World War I, another avant-garde arose in Zurich, New York and Berlin: Dadaism (circa 1916-1920s). Futurism threw itself at the promises of modernity; Dada, in contrast, set out to smash them. Dada artists rebelled against the rationality that had led to war; they created “anti-art” — absurdist performances, nonsense poems, collages of trash — to shock and upend bourgeois sensibilities. In doing so, they directly attacked the authority of art institutions and the concept of inherent value in art.

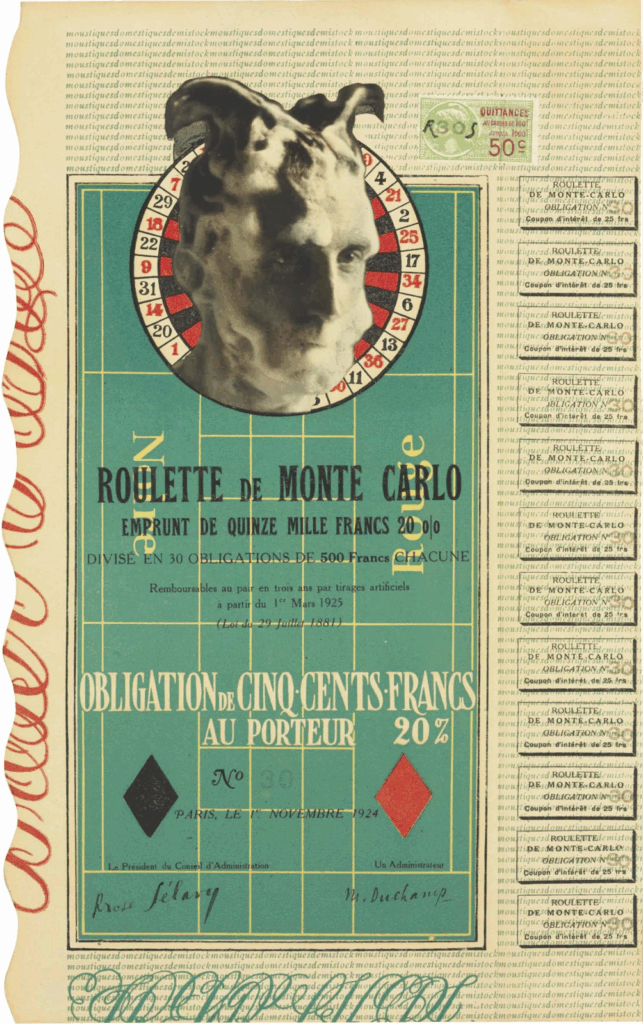

The familiar example is Duchamp’s “Fountain” (1917), but an equally revealing case is his Monte Carlo Bonds (1924): printed bearer “securities” issued in a planned edition of thirty, each priced at 500 francs and designed to raise capital for a roulette “system” Duchamp claimed to have perfected. The bonds looked and read like legitimate financial instruments — complete with detachable dividend coupons, corporate statutes on the verso and Man Ray’s photograph of Duchamp with shaving-foam “horns” inside a roulette wheel — but were staged as artworks. The company’s chair was Duchamp’s female alter ego, Rrose Sélavy; the administrator, Duchamp himself. Buyers were, in theory, investors; in practice, they treated the sheets as art objects, leaving every coupon uncut. The piece collapses two regimes of value — finance and art — and exposes the same underlying mechanism: value is not intrinsic, it is a social contract sustained by trust, scarcity and rules. Duchamp even paid a token interest once before abandoning the gambling scheme, an elegant reminder that the belief structure around the object quickly outstripped any cash flow it could ever yield.

Dada’s irreverent destruction of logic and value systems sowed seeds that later artistic (and even financial) revolutionaries would harvest. Later, Cypherpunks and Bitcoiners would challenge the fairness of the financial order; the Dadaists had already mocked the so-called rationality of polite society. They revealed that what people accept as valuable — whether a work of art, a bond certificate or fiat currency — might just be a shared fiction propped up by authority. In Dada, we see the prototype of Bitcoin’s ethos of challenging institutional authority: If Duchamp showed a urinal or a satirical bond could be “art” through collective agreement, Bitcoin showed that a piece of code can be “money” through collective agreement.

Notably, Dada was also inherently international and decentralized. Its artists (Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, Hannah Höch, etc.) were dispersed across Europe and the U.S., yet connected via manifestos, magazines and mail. This early 20th-century art network operated outside state or museum control — effectively a proto peer-to-peer network of creative exchange. In the way Dadaists mailed ideas and manifestos to each other across borders, we can glimpse the later ideal of a decentralized, censorship-resistant communication system.

ZERO: Building with Rules

By the late 1950s, Europe’s postwar avant-garde was looking for a clean slate. In Düsseldorf, Heinz Mack and Otto Piene founded ZERO (1957), soon joined by Günther Uecker. “Zero” for them wasn’t nihilism; It was a reset, a way to sweep aside the subjectivity of earlier modernism and construct art from scratch, using only light, rhythm and repetition.

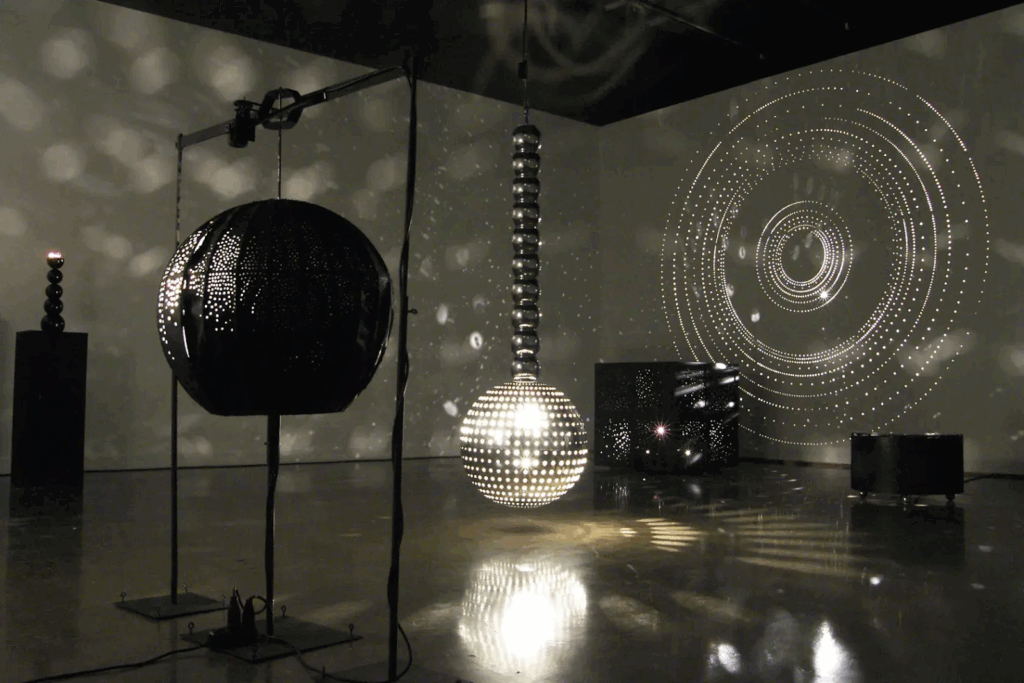

ZERO’s works were precise and repeatable: Piene’s “Lichtballette” used mechanical projectors to choreograph moving patterns of light; Mack constructed mirrored reliefs and spinning discs to create optical vibration; Uecker covered surfaces with dense fields of nails, turning hammering into a serial procedure. The art was in the process — the timed flicker, the rhythmic rotation, the grid of repeated forms.

Equally important, ZERO was never a closed group but an international network, linking to parallel movements in the Netherlands (Nul), France (GRAV) and Italy (Azimut). Exhibitions and collaborations spanned multiple countries, operating more like a decentralized platform than a single “school.”

For Bitcoin’s lineage, ZERO offers two resonant ideas. First, the reset: Starting from “zero” to construct a system by explicit rules recalls the symbolic reboot of Bitcoin’s Genesis Block. Second, the focus on time, repetition and seriality anticipates a culture attuned to protocols — systems where outputs arrive at fixed intervals and cumulative sequences matter.

Network Art: From Mail to Fluxus to the Net

While ZERO was exploring rules and serial processes, other artists of the 1960s turned toward communication itself as a medium. Their works made art into a distributed process, shared across people and places, outside the control of galleries or states.

One form was Mail Art, pioneered by Ray Johnson in the early 1960s. Small drawings, collages and notes circulated through the postal system, creating an “Eternal Network” of participants. Anyone could join; the post became a decentralized gallery where no curator decided who belonged. In Eastern Europe and Latin America, Mail Art even slipped under censorship, showing how a simple network could resist centralized control.

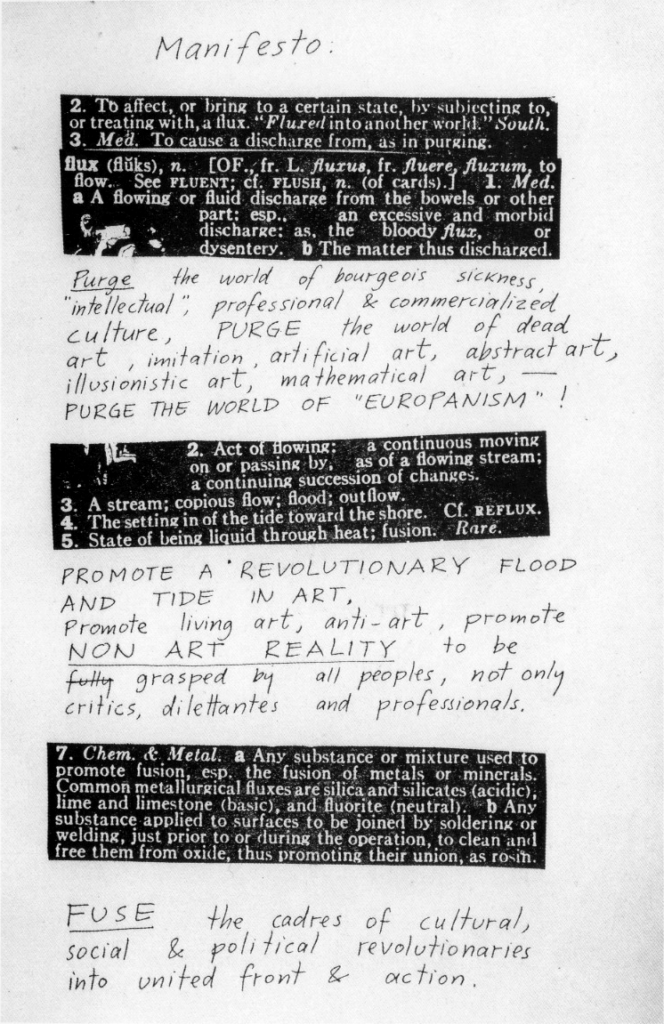

In parallel, Fluxus, led by George Maciunas and a loose international circle, declared that anyone can make art. Their performances, event scores and “fluxkits” were cheap, reproducible and often humorous — designed to evade traditional collecting and institutional ownership. Fluxus was art as open source action: participatory, irreverent and spread through informal networks of friends and collaborators.

By the 1990s, these impulses migrated online with Net Art. Early internet artists used chatrooms, email and websites as venues for collaborative works that were interactive, ephemeral and uncollectable in the traditional sense. Net Art made the network itself the artwork.

Mail Art, Fluxus and later Net Art all treated the network itself as a stage. Letters, performances, websites — each bypassed the gatekeepers of museums and markets, proving that exchange could be free, horizontal and self-sustaining. Bitcoin builds on that same intuition: validated by the network, not an institution.

Conceptual Art and Algorithmic Thinking: From Ideas to Code

By the late 1960s, avant-garde art took a radical turn: The object itself was no longer essential. In conceptual art, what mattered was the idea or instruction. Sol LeWitt wrote in 1967 that “the idea becomes a machine that makes the art.” His “Wall Drawings” consisted of sets of directions — lines, arcs, grids — executed by others. The authorship resided in the rule, not in the handcrafted product. The point was profound: Art could function like a protocol, a system anyone could run.

Almost at the same moment, artists began to make that principle literal. Algorithmic art translated imagined rules into actual computer code. Vera Molnár, for example, programmed early plotters in the 1960s to produce abstract line drawings. These works were generated rather than drawn; their originality lay in the algorithm itself. She described her method as a machine imaginaire, where systematic variation could produce surprising forms.

Seen together, these two practices created a cultural shift. Conceptual art established the logic that the work is the instruction rather than the object, while algorithmic art showed how that logic could be executed in code — precise, repeatable, and indifferent to the hand of the maker. Bitcoin fuses both. It is at once a conceptual protocol — rules inscribed in advance, like a score — and a piece of running code executed by miners and nodes, who perform the role of LeWitt’s assistants or Molnár’s machines: They don’t invent, they follow instructions. This lineage prepared audiences to see systems and protocols themselves as creative and valuable forces. Without it, the idea that an immaterial construct like Bitcoin — a set of rules enforced by code — could carry real value would have been harder to imagine.

Avant-Garde Time: On Kawara and Hanne Darboven

If conceptual and algorithmic artists turned rules into art, others in the same era turned to time itself as their system. Few bodies of work make the analogy to blockchain more striking than those of On Kawara and Hanne Darboven.

Beginning in 1966, On Kawara painted dates — plain white text on monochrome canvases — in his ongoing “Today Series.” Each painting had to be completed on the date it depicted; if not, it was destroyed. Often it was stored with a local newspaper, a kind of analog timestamp. Alongside this, Kawara logged every person he met (“I Met”), every route he took (“I Went”), the times he rose each morning (“I Got Up” postcards) and telegrams that declared simply: I am still alive. What emerged was a strict, cumulative chronology of existence: day after day, block after block, a sequence of proofs that life had occurred.

Hanne Darboven, working in Germany, went even further. From the late 1960s she devised numerical systems that translated calendar dates into endless handwritten sequences of sums, columns and grids. Her installations stretch across entire walls — hundreds of sheets filled with notations representing days, months, decades. Darboven turned the passing of time into a literal record of numbers, an unbroken chronology with no story beyond the sequence itself.

Seen together, Kawara and Darboven reveal how time, repetition and documentation can become both material and meaning. Their work anticipates exactly what Bitcoin later encodes. Each block on the chain functions like a Kawara date painting: a timestamp that proves the system is still alive. The sequence of blocks resembles Darboven’s endless grids, discrete units of time lined up to form an immutable chronology. And in both cases, meaning arises not from any single entry but from the accumulation of the whole chain. What Kawara and Darboven made visible is that even the simplest act of marking time can take on depth when repeated and preserved.

Systems and Power: Institutional Critique and Currency Hacks

While some artists turned inward to rules and time, others in the late 1960s and ’70s turned outward to expose the hidden systems of power — financial, political, institutional. Their work shows most clearly how art anticipated Bitcoin’s impulse to bypass authority.

In New York, Hans Haacke set out to reveal how money and power shape culture. For his 1971 project “Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real-Time Social System” he used public records, maps and photographs to document the slum properties of a major real estate network in the city. The work was scheduled for a solo show at the Guggenheim, but six weeks before opening, the museum canceled the exhibition and dismissed the curator. No direct link between the landlords and the museum was ever established, but the cancellation itself made Haacke’s point: Institutions are never neutral and attempts at transparency can be too uncomfortable to display.

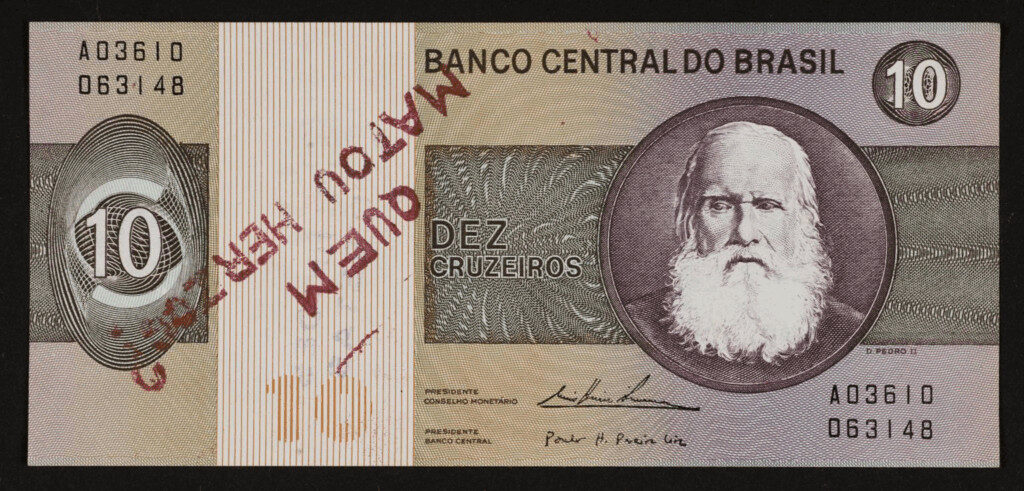

In Brazil, under dictatorship, Cildo Meireles developed a quieter but equally radical tactic. His “Insertions into Ideological Circuits” (1970) placed dissenting messages into everyday exchange systems. On Coca-Cola bottles, he silk-screened political slogans that only appeared once refilled; the bottles then reentered circulation. In his “Banknote Project,” he stamped questions like “Who killed Herzog?” (after a murdered journalist) onto currency, then spent the notes back into the economy. The system — Coca-Cola’s distribution, the state’s money supply — became the medium for critique. Meireles demonstrated that even a currency could be hacked into a carrier of counter-authority.

For Bitcoin, the resonance is unmistakable. Meireles’s stamped banknotes foreshadow the idea of embedding messages in a financial system itself — Satoshi Nakamoto’s Genesis Block inscription (“Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks”) is a direct continuation of that gesture. Both artists understood that systems are never neutral: They embody ideology. By inserting new content or exposing hidden structures, they revealed how authority could be challenged not with slogans alone but by repurposing the system against itself.

Bitcoin pushes that artistic lesson to its limit. Haacke revealed hidden structures and Meireles hacked messages into the circuits of money, Bitcoin doesn’t just comment on the system, but builds a new one. It inherits Haacke’s demand for transparency by making every transaction publicly visible on the blockchain and it carries forward Meireles’s spirit of subversion by creating a parallel currency outside the reach of state control. What had once been artistic interventions now scales into a global protocol. It’s not a metaphor about money, but a functioning redesign of how money itself can work.

Bitcoin as the Cultural Consequence

Looked at together, these movements tell a story that runs straighter than it first appears. Futurism celebrated the rhythm of machines; Dada stripped away institutional authority and showed how value depends on agreement; ZERO started again from light, rules and repetition; Mail Art, Fluxus and Net Art turned networks into the work itself; conceptual and algorithmic artists shifted attention from objects to protocols and code; On Kawara and Hanne Darboven treated time as something to be marked and accumulated, day by day; and Haacke and Meireles showed how power systems could be exposed or quietly hacked from within.

Each of these experiments rehearsed ideas that Bitcoin later fixed in its code: decentralization, rules over rulers, value as consensus, transparency as a form of truth, time as structure and the use of systems themselves as instruments of critique. None of this arrived out of thin air in 2009. For decades, artists had been testing the same ground — whether in paintings, instructions, mail networks, grids of numbers or altered banknotes — long before those intuitions were written into code.

None of this replaces Bitcoin’s technical invention. Proof-of-work remains the foundation that makes the system unforgeable, but it does not explain why people choose to protect and transact with it. This is why it misses the mark to see Bitcoin only as a financial tool or to dismiss its cultural dimension as a side story. Bitcoin is also a cultural artifact, shaped by a long history of challenges to authority and experiments with rules and systems. You don’t need to like art to see that. What Bitcoin embodies is not an isolated breakthrough but the continuation of ideas rehearsed for more than a century. Recognizing that history does not weaken Bitcoin’s invention; it roots it in a broader cultural lineage. Bitcoin is not an accident of code but the latest chapter in a century-long attempt to imagine systems beyond authority, to bind time into structure and to prove that value is ultimately what we choose to share and defend.

BM Big Reads are weekly, in-depth articles on some current topic relevant to Bitcoin and Bitcoiners. Opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine. If you have a submission you think fits the model, feel free to reach out at editor[at]bitcoinmagazine.com.

This post The Avant-Garde and Bitcoin: Decentralized Money Didn’t Come From Nowhere first appeared on Bitcoin Magazine and is written by Steven Reiss.